Transylvanian Hounds

and Vizslas—Different but the Same

By Scott Maze-

Five years ago we acquired Hannah, a Transylvanian Hound

puppy (in Hungarian, erdélyi kopó) purely by chance, just to save her from

going to the pound. We already had one

dog, but Hannah opened a whole new world for us. She led us to Puerto Rico, where she won her

pedigree, to new friends and to Hungary and Transylvania, where her breed

began.

Transylvanian Hounds share a common ancestry with Vizslas,

the two breeds probably diverging in the early Middle Ages. These dogs descended from the Asian hounds

accompanying the Magyars when they arrived in Transylvania in the 900’s. Those hounds mixed with local dogs and the

Celtic Hounds of the Romans. While

Vizslas developed along different lines, Kopós were used to hunt large game

such as bison, bear, deer, boar and lynx in the heavily forested slopes of the

Carpathian Mountains that ring Transylvania on three sides. Both breeds were pretty much the exclusive

property of the Hungarian nobility, who used them over the centuries for sport hunting

all over Transylvania. With only a small

number of owners, there must not have been many of these dogs even in the best

of times.

Kopós hunt in packs of no more than four, sent out alone to

flush the game and drive it back toward the hunters for the kill. Kopós have been known to cover as much as one

hundred miles in a single day during a hunt.

The hounds do not attack the game, they worry it into moving toward the

hunters instead of toward safety. Depending on the sounds made by their hounds,

hunters can tell the type and condition of the game coming toward them.

The good times for hunting began to end in 1918, the power

slipped away from the Hungarian nobles. After that

date, the popularity of hunting for sport must have declined and with it the

numbers of these dogs as well. Less than

twenty years later, World War II marked the final end of the good times for the

owners of both breeds. At the War’s end,

the arrival of the Russian Army in Transylvania meant the installation of a communist government, while Hungary suffered the same fate.

The Communists set about destroying all images of the power

and supremacy of the Hungarian ruling class.

That policy resulted in the 1947 edict that all Vizslas and Kopós were

to be eradicated (the official excuse was that they damaged crops and game). By the mid-1960’s, the few Kopós left in

Transylvania were hidden deep n the recesses of the Carpathians, while the few

Vizsla in the world had apparently been spirited out of the country years

earlier. From 1944 to 1968, no Kopó

puppies were recorded as being born (the few births were apparently kept

secret).

In the mid-1960’s, however, a few Kopós were smuggled out of

Transylvania by some intrepid Hungarians. With those few dogs, the Hungarians began a

revival that is still underway. And

since the fall of their Communist government in 1989, Transylvanians--both

ethnic Hungarians and Rumanians--have begun to slowly join in that revival.

Today, there are still less than one thousand Kopós left, with

a much smaller number of actual breed stock. But we are picking up the beat

here in the U.S. Worldwide last year,

about one hundred Kopó puppies were registered for pedigree with the FCI, all

of them born in Hungary or Transylvania.

This year, twenty puppies have already been registered in the U.S. and

the prospects for 2014 are even better, with the number of breeders expected to

double.

Hannah and her Hungarian mate Avar (now a U.S. citizen) are

the parents of eight of those puppies, the first U.S. litter ever registered

for FCI pedigree and the start of our own breeding colony, called California

Transylvanians. We are working closely

with other breeders in the Transylvanian Hound Club to help with the revival of

this breed in a way that preserves its qualities, which have not changed in a millennium.

So, what makes Kopós worth saving? First, they are an ancient breed, virtually unknown

outside their native land and relatively unchanged in over a thousand years,

unlike so many breeds today. Second,

they are bred to hunt but they are very mellow.

They are still used today to hunt wild boar in Transylvania, but at home

they are warm, affectionate and easy-going.

A Kopó forms a strong personal attachment that does not change once

established. They learn quickly and excel at recognizing

patterns—a Kopó barks at the mailman the first time, but never after that. They are cautious—they don’t charge into a

fight—but they are courageous when the need arises. And they are simple, beautiful, clean-lined

animals with short coats who thrive in heat and cold.

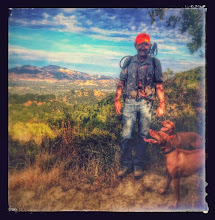

Five years after Hannah’s arrival, we happily live and play

with a pack of four, including her mate and two eight-month old puppies from

her first litter, with more litters planned.

When people ask why we didn’t just save a “pound puppy”, we tell them we

are saving an entire breed!